Autorretrato como Seri, Desierto de Sonora (Self-Portrait as Seri, Sonoran Desert), 1979

By Briá Purdy

In her essay “Mediated Worlds: Latin American Photography”, Amanda Hopkinson tells an anecdote about André Breton, who, when he first saw an image by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, ‘congratulated the Mexican people on being ‘natural surrealists.’’1 It is a sentiment he later echoed in reference to the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, to which she somewhat ironically responded: ‘I didn’t know I was a surrealist until told so by André Breton’.

Breton’s statements are symptomatic of paternalistic attitudes towards the condition of Mexican art, Mexican artists, and, more broadly, a diluted and entirely European vision of the state of Mexico itself. Following the Mexican Revolution in the early twentieth century, many demanding questions arose about how to reconstruct a new national identity. The struggle for Mexicanidad continued as an identity forged by a renewed interest in Mexico’s indigenous cultures, but in the post-revolutionary era, this rediscovery of pre-Hispanic identity was born paradoxically of fascination and discrimination. What’s more, state-funded financial support for the arts favored an art which glorified nationalist values within the new democratic politics. The preservation of marginalized traditional cultures was one approach to creating a new, hybrid national identity. Artists, especially artists working in metropolitan areas, therefore became increasingly motivated (both professionally and financially) to explore and document these cultures as a means of interrogating the essence of Mexican identity. An avant garde artistic movement of Mexicanidad emerged, forefronted by artists like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. The contributions made by female artists to the movement, although their part in the revolution was hardly recognized, cannot be ignored. There are two major photographers who were crucial in reconstructing Mexican national identity: Graciela Iturbide and Lola Álvarez Bravo.

Museum of Modern Art, New York.

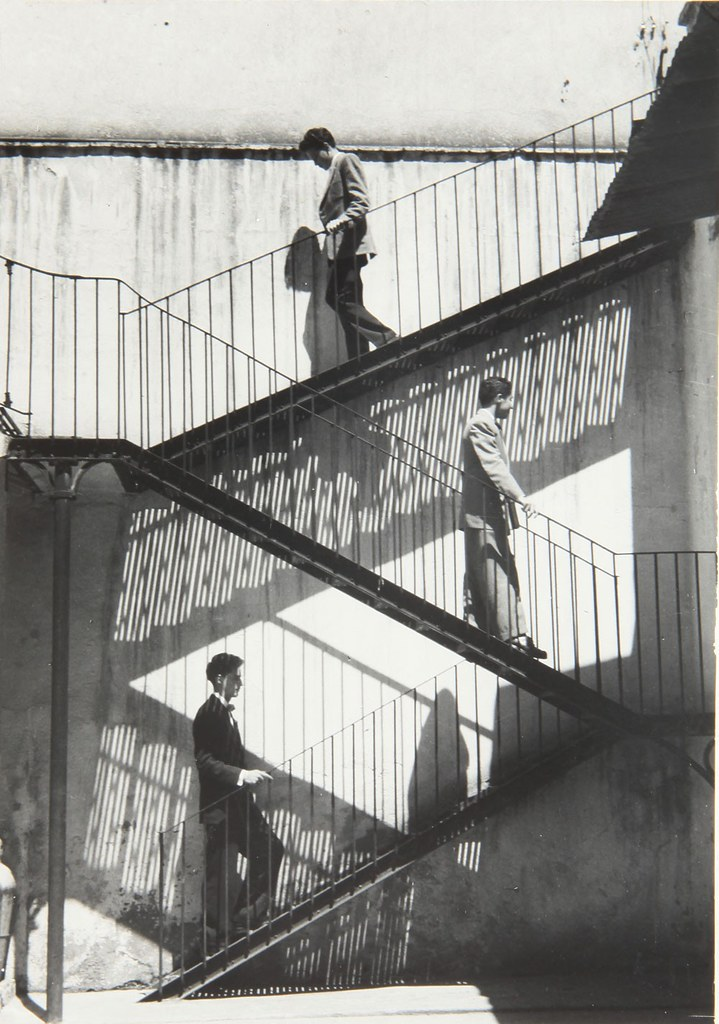

Born 1942 in Mexico City, Graciela Iturbide was the eldest of thirteen children brought up in a traditional Catholic family. Getting her first camera at age 11, she later pursued cinema at university and it was there that she would first meet Manuel Álvarez Bravo. A teacher at the university, Álvarez Bravo would later become Iturbide’s mentor and friend. Traveling with him to rural villages, she was introduced to photography following his hay tiempo approach, a methodology of patience in waiting for subjects to appear. Through their travels, Iturbide witnessed many aspects of indigenous Mexican life, adopting from Bravo this humanist method of documentary photography. Iturbide was interested in portraying indigenous Mexican cultures, and specifically the women within these often marginalized communities, with this technique. Through her work, Mexico is stationed as the central site of a revolutionary avant garde, influenced on one hand by the influx of exiled European artists settling in Mexico, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, and on the other hand, the development of a distinctly un-European, Mexican modernist aesthetic, developed by Manuel Álvarez Bravo.

Born almost 40 years earlier than Iturbide, in 1907, Lola Álvarez Bravo had an established and successful career in Mexico. Also taught and influenced by her husband, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Lola Álvarez Bravo developed her own photography style and, long after the couple separated in 1934, continued to create her own artistic legacy. Like Graciela Iturbide, Lola Álvarez Bravo’s interest lay in documentary-style, through which she chronicled the vast diversity of Mexican indigenous cultures, always with a humanistic perspective.

Although evidently inspired by their male contemporaries, Lola Álvarez Bravo and Graciela Iturbide went further in their humanistic portrayal of, and their commitment to preserving, the vast traditions and cultural heritage of Mexico’s indigenous peoples. In the photograph, Autorretrato como Seri (Self-Portrait as Seri), Iturbide portrays herself made-up in the traditional face painting worn by the Seri women of northwest Mexico. Commissioned by the government to document the changing nature of Mexican traditions, Iturbide traveled to the Sonoran Desert in 1979, where she observed and lived among the Seri people. Not only does this self-portrait testify to her acceptance into the Seri community, but it also acts as an interrogation of her role as photographer. Just as she captures the lives and rituals of these people, so is she willing to turn the lens on herself, in order to truly understand their customs and ways of life, not simply to document them as a token of ‘otherness’. Robert Tejada wrote in his 1996 essay, “Graciela Iturbide’s images are powerful because they underline time and again the rift between belonging and citizenship… These images speak of outsider culture within larger constricting divisions.”2 She is not an objective, but a deeply subjective photographer, and it is precisely because of her subjectivity that her images are more than the objects themselves. In the book Graciela Iturbide, Cuauhtemoc Medina highlights that although her work has often been equated in exoticized Occidental terms with a form of visual ‘magical realism’, her work is also “a personal quest for identity, and is based in great part on the experience of sharing the life and the sorrows of her sitters.”3 In other words, Iturbide’s images have something to say about the state of a diverse and fractured nation because she refuses to stay out of the picture and instead puts herself, with the sitter, into the frame.

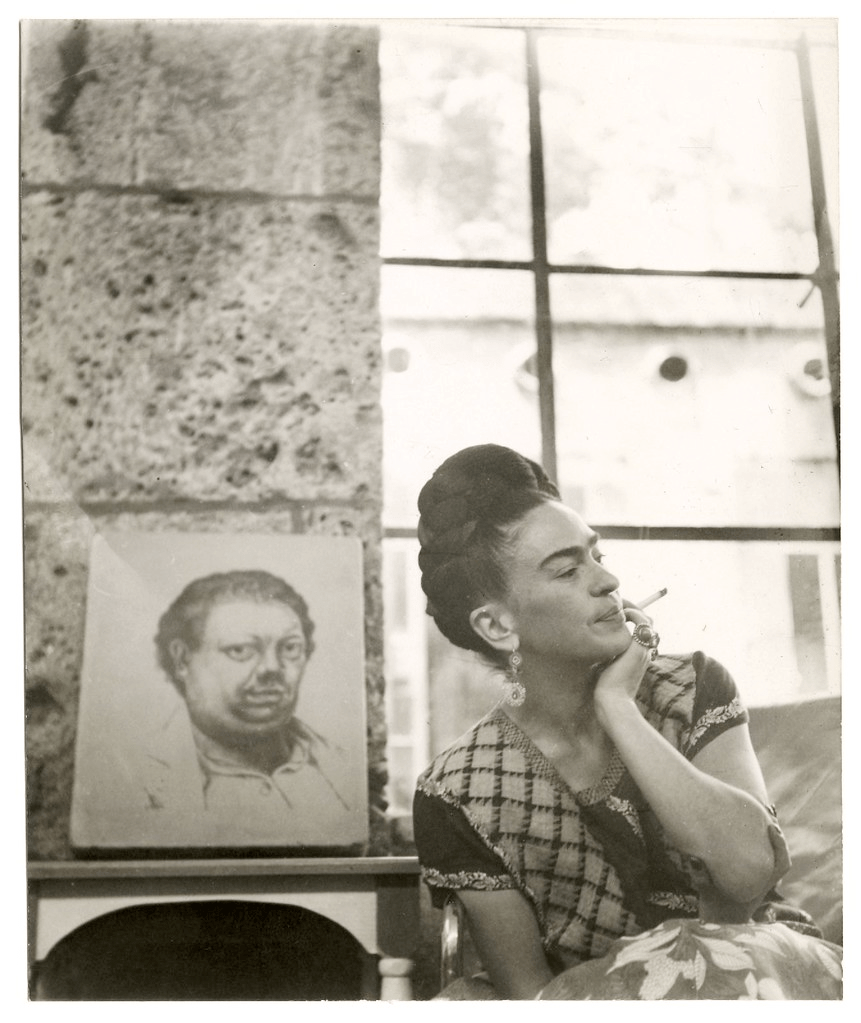

Reciprocity of gaze between photographer and subject is something Lola Álvarez Bravo explored through her lifelong friendship and artistic collaborations with Mexican artist, Frida Kahlo. Through her images of Kahlo, who was often dressed in traditional Mexican clothing and wore her hair in braids, Álvarez Bravo translated the re-surging importance of Mexicanidad in post-revolution Mexico. Just as Graciela Iturbide presented herself in Self-Portrait as Seri, in photographs such as Frida in Front of Mirrored Wardrobe Keeper, 1944, Álvarez Bravo presents the duality of modern Mexican female identity. In this photograph, Kahlo appears twice: once in profile, leaning against a large stone wall; the second time she is reflected in the arched mirror, and it is through her reflection that we most clearly see her face. Duality is a theme which runs through not only Álvarez Bravo’s photograph but also Kahlo’s own painting. There is a synthesis of identity between artist and subject, a reflection (quite literally) of the artist as she sees herself, and as she is seen by the camera and by the world. Similarly to Iturbide’s self-portrait, in this photograph there is a connection between Mexico’s past and the present, characterized by a desire, not to objectify or fetishize, but to become. In an interview in 1989, Álvarez Bravo described Kahlo as “a Mexican mood concentrated in an epoch.”4 Kahlo’s adoption of traditional Tehuana clothes symbolises a revived desire to reclaim the nation’s indigenous identity in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. Her image (now an iconographic totem all of its own) reflects how “Mexico’s indigenous heritage was placed at the very centre of the new representations of national identity being constructed by the new regime’s leading intellectuals.”5

Two years later, in 1946, Álvarez Bravo traveled to the southern state of Oaxaca to photograph the indigenous Zapotec people. The resulting photograph, Entierro de Yalalag (Burial at Yalalag), is a somber account of the funeral procession in which the Zapotec women walk alongside the hoisted coffin carried by the men. The women’s faces are obscured, their heads covered in long, ethereal scarves, which stand in contrast to the dark, rocky landscape which fills the horizon line. The lyrical composition follows their funeral march, leading the viewing eye from right to left across the mountainous terrain, suggesting what it means to walk from life into death. The carefully captured documentation of this cultural ritual stands as a testament to the endurance of these indigenous traditions within the ever-changing context of 20th-century Mexico.

In 1978, Graciela Iturbide set out on a similar pilgrimage, commissioned by the ethnographic archive of the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico, to work on her first series about the Seri people. During this trip, Iturbide captured one of her most renowned photographs, Mujer Ángel. This image embodies many of the recurring iconographies and subject matters persistent in Iturbide’s work. An angel of death appears from the left of the frame, though we cannot see her face. She is a traditionally-dressed, atemporal figure who sanctions our limited access to this acrid land. We may only glimpse under her raised arms and into another world entirely. A sprawling and intoxicating geography of Mexico, presented through the people, the traditions, and the cultural practices. As Iturbide described it: “I went with a group to a cave where there are indigenous paintings. I took just one picture of this woman during the walk there. I call her Mujer Ángel because she looks as if she could fly off into the desert. She was carrying a tape recorder, which the Seris got from the Americans, in exchange for handicrafts such as baskets and carvings, so they could listen to Mexican music.”6

But this Mujer Ángel, who is she? Is she a fleeing woman? A phantasmic apparition returning to a familiar and arid land? Her arms lift like wings, turning her into a bird, symbolizing the transition between land and sky, between this plane and another. In that singular and otherworldly-moment, an object reconfigures her surroundings. A stereo poised like a harbinger of the horizon line, cutting the image in half, bringing us back to the present. A fleeting moment, captured by deft hands, transmitting the import of American culture onto the Mexican landscape, a moment of convergence between the modern and ancient worlds. Iturbide’s photograph is perhaps a perfect example of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographic philosophy of the “decisive moment,” the moment when the visual and emotional elements of reality align in perfect synchrony.7

Museum of Modern Art, New York

In contrast to this convergence is the photograph De generación en generación (From Generation to Generation), 1950, by Lola Álvarez Bravo. Similarly to Mujer Angel, the central figure in this image is an indigenous woman who appears with her back to the camera, her face obscured from the viewer. She is wearing a black wool skirt and woven belt indicative of the indigenous communities living in south-central Mexico, called Morelos. Over the woman’s shoulder appears the face of a baby, unsmiling, dark eyes staring intently into the camera’s lens. In De generación en generación (From Generation to Generation), the focus on motherhood is evident, and, unlike in Mujer Angel, where the presence of the boombox suggests the creeping technological influence of a modern-day Mexico, here, there are no signs of post-revolution. The artist herself said of her work: “If my photographs have any meaning, it’s that they stand for a Mexico that once existed.”8 Here, within the frame of the photograph, time seems to stand still. We are projected into an essential representation of Mexicanidad, of what it means to hold onto a traditional Mexican identity in a changing and ever-evolving political and technological state. In the photograph, Álvarez Bravo perhaps juxtaposes the paternalistic nationalist context with an overwhelmingly maternal expression of emotion, signaled by the faceless mother holding her child tight. Hers is the only face we see, and her stoic gaze is both poignant and haunting.

Both Lola Álvarez Bravo and Graciela Iturbide worked all of their lives documenting the lives of indigenous Mexican communities with compassion and respect. They refused to prescribe, as André Breton had, an identity to their subjects. Instead, through their photography emerges a desire to transmit reality not as an objective truth, but as a subjective understanding of individual experience. And it is perhaps through this individual experience, a small but significant part of the whole, that a national identity can be constructed. One photograph at a time.

Briá Purdy is an art writer and multidisciplinary artist. Born in Manchester, in the North of England, she moved to Scotland to study History of Art and French at the University of Edinburgh, where she graduated in 2022 with a First Class Honours Degree. Briá is a co-founder of Fairly Current, a multilingual arts and cultures blog. She is also the editor of The Head of a Woman, a surrealist print zine. Briá’s approach to writing fuses personal style with an art historical subject matter to create an accessible and intimate portrayal of a diverse range of artists as relatable figures for contemporary readers.

1. Amanda Hopkinson. “‘Mediated Worlds’: Latin American Photography.” Bulletin of Latin American Research, vol. 20, no. 4, 2001, pp. 522-3. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3339027. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

2. Roberto Tejada. “Sidelong Mirrors and Invisible Masks. The Photography of Graciela Iturbide.” Images of the Spirit: Photographs by Graciela Iturbide. New York: Aperture Foundation, 1996, pp. 12-13.

3. Cuauhtemoc Medina. Graciela Iturbide. Phaidon, 2001. p. 4.

4. Lola Alvarez Bravo, quoted in Salomon Grimberg, Lola Alvarez Bravo: The Frida Kahlo Photographs. Washington, D.C.: National Museum for Women in the Arts, 1991, p. 7.

5. Edward J. McCaughan. “Social Movements, Globalization, and the Reconfiguration of Mexican/Chicano Nationalism.” Social Justice, vol. 26, no. 3 (77), 1999, pp. 61-2. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29767161. Accessed 31 Mar. 2025.

6. Image description, Mujer Ángel / Angel Woman, Sonora Desert, High Museum of Art, Atlanta. https://high.org/collection/mujer-angel-angel-woman-sonora-desert/. Accessed 1 Apr. 2025.

7. Henri Cartier-Bresson. “The Decisive Moment.” Simon & Schuster, New York, 1952. 8. Leslie Sills. “Lola Álvarez Bravo (1907-1993)”. In Real Life: Six Women Photographers. New York, New York: Holiday House, 2000, pp. 31-39. ISBN 0-8234-1498-1.