By Alessandro Columbu

Although first published in 1999, Edward W. Said’s Out of Place feels uncannily contemporary. Said’s prose retains a clarity and ethical attentiveness, a book whose voice continues to speak in an extraordinary eloquent tone, directly to the present. It is a memoir of displacement that resists the conventions of self-justification but unfolds as a sustained act of self-interrogation. Out of Place is at once a personal testimony and a reckoning with memory, language(s), family, and formation. The historical weight of the life it recounts, the honesty with which Said allows contradiction, discomfort, and emotional opacity to remain unresolved, all meant that I couldn’t put it down the moment I started reading it.

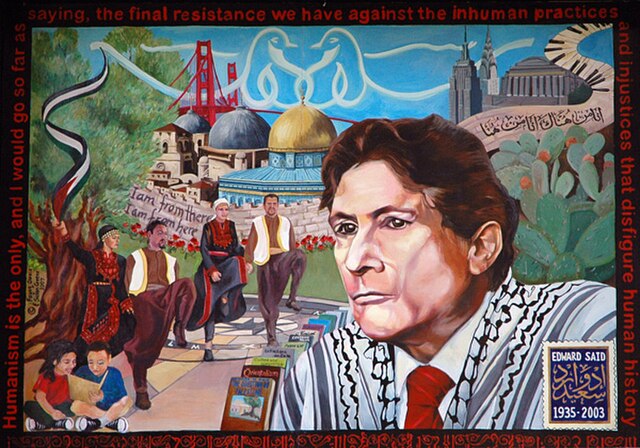

Born in Jerusalem in 1935, raised largely in Cairo with summers spent in Lebanon and Jerusalem (until 1948, at least), and educated in elite colonial British and American institutions, Said narrates a life structured by constant misalignment. The title Out of Place names a condition of exile as well as a temperament, a way of being in the world defined by vigilance, self-correction, and an enduring sense of not quite belonging anywhere. This sensibility, which later readers recognize as foundational to his critical work, is here traced back to its intimate origins in childhood, family dynamics, schooling, and early desire.

The memoir is written late in Said’s life, after his reputation as a public intellectual had long been established, and yet it contains none of the self-congratulation one might expect from a figure of his stature. On the contrary, Said repeatedly undermines his own authority as a narrator. Memory is presented as partial, emotionally charged, and sometimes suspect. The self that emerges is fractured, frequently embarrassed by its own past ambitions, cruelties, and evasions. This refusal to smooth over the self is one of the book’s most compelling ethical gestures.

History with a capital H is present in Out of Place in the erasure of a home never fully inhabited, in the sudden transformation of familiarity into estrangement, and in the quiet normalization of injustice that accompanies colonial order. The Nakba appears not as a sustained historical account but as a background trauma that intermittently surfaces through memory, displacement, and loss. Said does not stage the Nakba as spectacle. Instead, he masterfully allows it to seep into the narrative through absence, through the disorientation of borders that shift without consent, and through the emotional inheritance of a catastrophe that is both collective and personal.

This approach is consistent with the memoir’s overall structure. Out of Place moves associatively, never as a linear coming of age story, circling certain relationships and experiences with increasing depth. Chief among these is Said’s relationship with his mother, Hilda. Few literary portraits of maternal intimacy are as unsparing or as tender. Said writes of her dominance, her emotional volatility, her ambitions for him, and the suffocating closeness that both sustained and constrained him. There is love here, but it is a love entangled with obligation and resentment. Consider the following passage as an example of how rare this level of self-exposure is, especially from a figure so often read through the authority of his public voice. Said allows himself to appear vulnerable and even diminished in the maternal relationship, without attempting to justify or stabilize it afterward. Exile is rendered not only as a political or geographic condition but as an affective one, first experienced in the intimate drama of leaving his mother and never quite returning to the place of her full approval.

In the summer of 1951, I left Egypt for the rest of my schooling in the United States. This included high school then undergraduate and graduate degrees, a total of eleven years, after which I remained until the present. There is no doubt that what made this whole protracted experience of separation and the return during the summers agonizing was my complicated relationship to my mother, who never ceased to remind me that my leaving her was the most unnatural (“Everyone else has their children next to them”) and yet tragically necessary of fates.

Each year the late-summer return to the United States opened old wounds afresh and made me re-experience my separation from her as if for the first time—incurably sad, desperately backward-looking, disappointed and unhappy in the present. The only relief was our anguished yet chatty letters. I still find myself reliving aspects of the experience today, the sense that I’d rather be somewhere else defined as closer to her, authorized by her, enveloped in her special maternal love, infinitely forgiving, sacrificing, giving because being here was not being where I/we had wanted to be, here being defined as a place of exile, removal, unwilling dislocation. Yet as always there was something conditional about her wanting me with her, for not only was I to conform to her ideas about me, but I was to be for her while she might or might not, depending on her mood, be for me. (Out of Place, p. 218)

What makes these passages so affecting is their refusal of easy moral resolution. Said does not seek to redeem or condemn his mother. He records her with a precision that suggests both devotion and exhaustion, where the mother figure becomes central to his early formation of self-discipline. Reading these sections, one recognises how profoundly family intimacy can shape intellectual temperament. The acute sensitivity to judgment that marks Said’s later prose is already visible in the child who learns to anticipate displeasure and to inhabit language as both refuge and defense.

Reading Out of Place for me inevitably called to mind Antonio Gramsci’s biography written by Giuseppe Fiori and his prison letters to his family, despite the obvious differences between their lives. Unlike Gramsci—whose family was of Albanian origin, who grew up in Sardinia in material hardship, and who later endured imprisonment at the hands of Mussolini’s regime as the leader of the Italian Communist Party—Said was Palestinian but Christian, raised within clear class privilege, in a well-off and culturally cosmopolitan family. Yet the emotionally charged relationship Said describes with his mother carries a similar urgency to the one I found in Gramsci’s correspondence. I found a need to speak with clarity and tenderness that arises from the pressure of historical circumstance and impending loss. This passage is from Gramsci’s first letter to his mother following his imprisonment, dated May 10, 1928: Life is like that, very hard, and sometimes sons must be the cause of great sorrow for their mothers if they wish to preserve their honor and their dignity as men. I embrace you tenderly.

Said’s memoir, though written in retrospect, conveys a comparable necessity to articulate what could not be said at the time, especially where the maternal bond is concerned. In both cases, writing becomes an ethical act, an attempt to give language to love and responsibility before silence hardens into permanence. The memoir’s treatment of sexuality is similarly candid and unresolved, especially when Said writes of desire with restraint but without evasion. Sexuality appears less as a site of fulfillment than as another register of dislocation. Desire is often marked by secrecy, anxiety, if not sheer incompetence. There is a sense that the body itself becomes another territory in which one is not fully at home.

In Said’s account of his years in the United States, the promise of intellectual freedom is shadowed by a profound lack of meaningful friendship and intellectual stimulation, particularly during his undergraduate years at Princeton in the 1950s. Despite professional success and academic distinction, he describes an emotional barrenness that contrasts sharply with the intense if fraught relational world of his youth. The American environment appears efficient but isolating. Friendship is formal, compartmentalized, often subordinate to career and status. Without romanticizing the places he precariously called home like Cairo and Jerusalem, he registers a loss of intimacy that exile cannot compensate for. This sense of being an outcast persists even in moments of apparent belonging. Whether in elite schools, Ivy League institutions, or public intellectual circles, Said remains acutely aware of difference. Accent, name, background, and political position all marked him, as well as fellow Arabs or Jews, as other, yet marginality never transforms into moral superiority. Instead, he portrays it as a condition of heightened self-consciousness. In other words, the outsider’s clarity is inseparable from his or her loneliness.

Throughout the memoir, music, particularly opera, functions as a parallel language of belonging. Said’s immersion in music is not incidental, offering him a form of structure, emotional articulation, and transcendence that neither family nor nation reliably provide. It is difficult not to see in Said’s musical sensibility the roots of his later attentiveness to form, rhythm, and counterpoint in both literature and politics.

This aesthetic formation matters. Out of Place makes clear that Said’s scholarly insights did not emerge in abstraction. They were shaped by a life lived across languages, cultures, and expectations. The discipline of close reading, the suspicion of authoritative narratives, and the insistence on historical context all appear here as lived necessities rather than theoretical preferences. His later critiques of Orientalism and imperial discourse can be traced back to the child who learned early how representation misaligns with reality, and how power operates through description.

At the same time, the memoir resists being read as a simple origin story for an intellectual career. Said repeatedly emphasizes uncertainty and failure. He describes his own moments of emotional withdrawal with a frankness that complicates any heroic narrative. This ethical rigor extends to his political reflections. While Palestine remains a central moral horizon, it is never instrumentalized as a means of self-absolution. The political and the personal remain in tension, refusing to collapse into one another.

After reading Out of Place, a sense of having encountered a mind that refuses consolation has remained with me. The book offers no redemptive arc, no final synthesis. For a reader, especially one attuned to itinerant lives and the aesthetics of displacement, the book resonates not only as Said’s story but as a meditation on modern subjectivity. The experience of being formed by multiple worlds without fully inheriting any of them is increasingly common. Yet few writers have articulated this condition with such linguistic precision and emotional restraint. Said’s prose remains elegant without being ornamental, disciplined without being cold, never seemingly demanding empathy. In this sense, there are moments when the memoir’s reserve can feel distancing and I often wished for greater warmth, for scenes of joy without the usual self-analysis. But the thing is: this absence is itself telling, because Out of Place is not a celebration of survival or success. It is a record of vigilance, of the costs of awareness, and of the labor required to live in a world that is never fully one’s own.

In the end, what makes Out of Place endure is its moral seriousness, its unwavering honesty. Said treats his own life as a text worthy of the same scrutiny he applied to literature and politics, always attentive to silences and contradictions. For readers, this is both demanding and generous, particularly in the ways it asks us to reconsider our own narratives of belonging, to question the comforts of identity, and to accept that coherence is not always attainable.

Alessandro Columbu is Senior Lecturer in Arabic at the University of Westminster. Originally from Sardinia, Alessandro learned Arabic in Syria, Lebanon and Jordan, and earned his PhD in Arabic literature from the University of Edinburgh.

Columbu’s recent translation of Critical Conditions: My Diary of the Syrian Revolution was named one of World Literature Today’s Best Translations of 2025. Prior publications include Zakariyya Tamir and the politics of the Syrian short story – Modernity, gender and authoritarianism published by IB Tauris. He won the 2023 edition of the Sheikh Hamad Award for Translation and International Understanding for his translation of Zakariyya Tamir’s Sour Grapes, published by Syracuse University Press.