By Carrie Paterson

In 2013, my art-science research practice was nearly derailed by chronic-recurring Epstein-Barr, a post-viral weakening of the immune system that is commonly associated with chronic fatigue, and which has many similar effects on a person as COVID “long hauler” syndrome. Mine was brought on by a severe flu and resulted also in myeloencephalitis. For years, I found conceptual thinking, sustained concentration and art-making difficult, but this experience opened a new portal into the potentially deep relationship between somatic art practices and human factors in astronautics.

My past work thematically has included a sculptural exploration of gravity, which morphed in the early 2010s into palliative solutions for astronauts and aids for human health in micro-gravity like olfactory stimulation and plant-human partnerships. The genesis of my current project is meditation research in sensory deprivation tanks, the closest civilian equivalent to the flotation tanks used by astronauts-in-training.

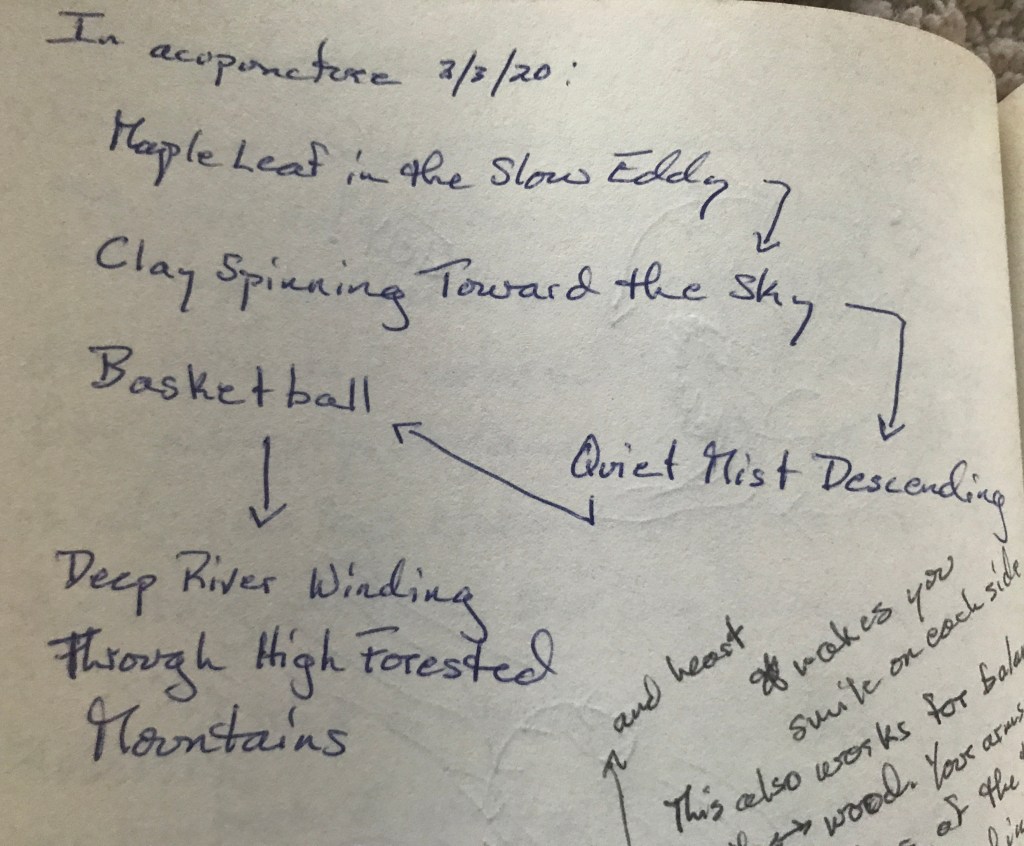

My methods are simple: I spend 30-60 minutes lying flat in water, notice the transitory movements in my body and later record my observations. I also do this in acupuncture sessions. In the tank experiences, but also in pools, the ocean, or a bath, I work with deep breathing and imagining specific movements made by sea life; for example, visualizing the bodies and habits of the octopus, the hammerhead shark, starfish, mollusks, jellyfish, nurse sharks, the giant squid, the porpoise, and imagining the surf moving over the bones of a beached whale.

These visualizations are becoming an extended personal library of Qigong (qi-work), a gentle Taoist method of harmonizing qi (energy) that I have learned from various teachers during my years of required rest. A martial art developed over many thousands of years, Qigong has been a healing practice since ancient times, when humans lived much closer to the laws of nature and developed art and science together out of cosmology.

“Qi” is a multi-dimensional word-concept that encompasses health, life-force, energy, vitality, breath, mastery, information, and skill, among other definitions. Qi is directional. It moves constantly. It exists in the earth, the ocean, the atmosphere, and circulates in every living thing. The visualizations that occur to me are images of nature’s processes, habits of animals, movements of human bodies, moments of beauty that I have seen in person, or through video/film/animation. In actively working with these images and transforming or refining them, I attempt to cultivate non-anthropocentric viewpoints, much like how the traditional movements are often named after revered or mythological creatures. In my own lexicon, what is taking shape is a transdisciplinary catalog of empathetic, somatic meditations.

Because the meditating mind starts to associate imagery, colors, shapes, and ideas with transitory physical sensations, we can become both observer and observed, using our own bodies as laboratories. This is a subjective science — something between art, narrative medicine, psychology, anthropology, and ecology. I hope one day, this kind of activity, refined, could assist human health off-planet by alleviating human isolation and alienation. If you’ve read this far, then I am sharing my experiences with you in hope that you will enter this dialog and together we can create something larger — working toward a collective haptic consciousness that centers environments and species.

My central questions in this project: How can the human body and mind adapt to living without Earth-gravity’s essential force? Can our minds recall the experience of gravity for our bodies? Are the effects of gravity encoded in our DNA as an epigenetic force? Do we require gravity to generate thought? Does our somatic intelligence rely on this force to develop? What happens to consciousness when gravity is removed for extended periods?

Based on my first strange and discomfiting experience in the weightlessness tank, which I will relate next, my hypothesis is that in microgravity astronauts may have an issue with “qi flow” — that qi doesn’t circulate properly because of a lack of gravity — which might contribute to their documented health problems. Lying flat against the earth (as in the yogic shavasana, “final resting pose”), the body achieves homeostasis. Seemingly required for this are also a source of heat, as otherwise being static in extremely low temperatures, we would certainly freeze. As opposed to any other kind of “work” we may do, in this lying rest, our autonomic nervous system is invigorated by us doing nothing, seeking nothing, being still. We already know that for the earth-bound, being deprived of this critical aspect of gravity-induced rest, as in torture or inhumane work hours, results in psychological and physical harm. Some of these problems are similar to astronauts’ issues with the eyes, sleep, mental health, digestion, bone density, and heart rhythm.

Around 2014, I was experimenting in a flotation tank with the sensations of one of the oldest series of Qigong movements called the Baduanjin (“Eight Pieces of Brocade”). Using my intention to guide my imagination of the movements without physically moving my body, as I had done many times before, I found something quite abnormal. In the tank, my qi would not flow; rather, it got “stuck” at the source point of the navel. I felt as if I were spinning around this point, or my body was clapping together at that hinge, or as if I were a clock, tick-tocking horizontally right and left, feeling like my head was swinging wildly back and forth to touch each foot, all while my feet seemed to be pointing toward magnetic north like the point of a compass (they were, in fact, pointing south-east). I remained completely still in the tank, which is quite small, and if I had been moving in any way, I would have touched an edge. It was a terrible experience, but I stayed inside of it to observe. When I emerged, I felt shaken.

But nothing worth doing is easy. I have since learned that in the philosophy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the qi is thought to originate in the navel when we are fetuses, that we receive qi from our mothers. We are floating and anchored to her through this point, and it is not until we emerge from the womb that our orientation (however uncomfortably) changes toward the earth. What was this dream I had years before, where I was floating in space, tethered to the Earth, and suddenly was yanked back? Falling through the clouds, rushing toward the ground, fearing my own death as I accelerated? I realized I was visualizing my connection to the Earth as a disaster, and the fear of being a body that can’t live anywhere else.

Perhaps that will turn out to be true. Yet, the viability of long-term space travel and space habitation may be an intermediary point. Maybe we can learn to exist in multiple realms. The entire field of cybernetics is built upon this principle of mind-over-matter, of training cognitive functions to achieve difficult goals. Yet, there is another critical aspect to this question: if many of our health problems are endemic to the human condition, which requires gravity, might we be able to design more healthful environments in space? How could those be brought to earth?

Here the role of the artist may be significant. Can the study and practice of “embodiment” be a kind of design tool?

I now ask you to consider a series of meditations, related to the above, before I continue to relate my experiences in the tank.

- “Dog on Sunny Grass”: Lie down and imagine yourself as a dog joyfully twisting on its back in some sunny grass. Your mouth is open, tongue and jaws loose, front paws loose against the chest, your tail and lower body twisting strongly back and forth. Do this in your mind’s eye for a while, or even physically perform the activity. See how you feel.

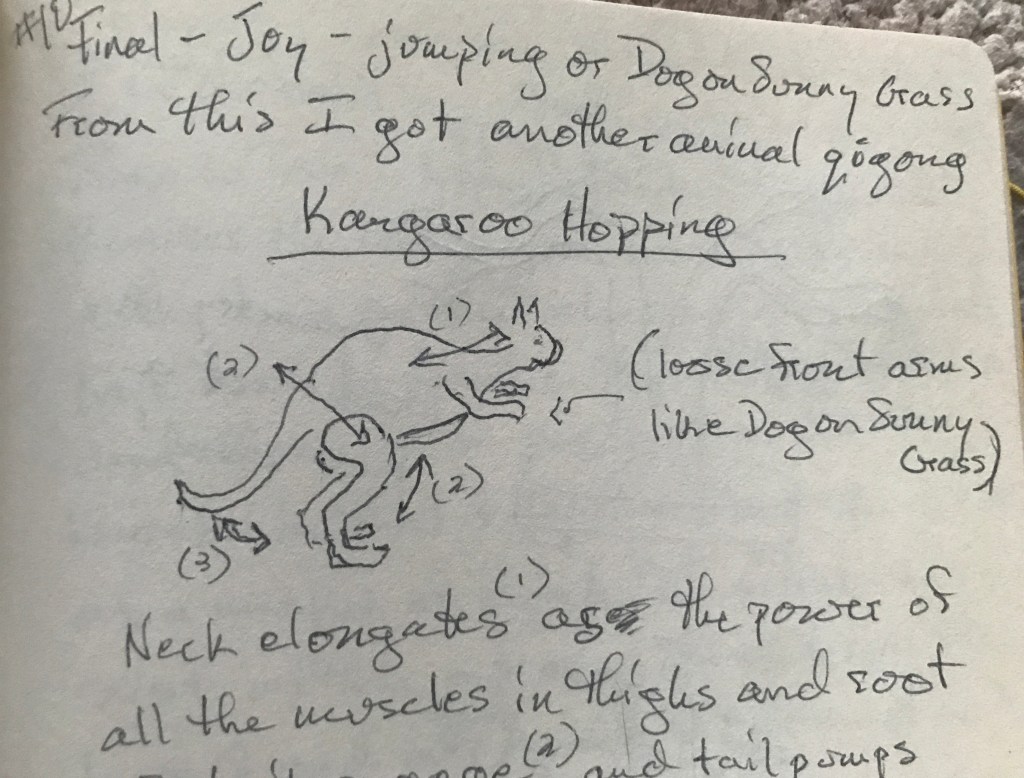

- Take what you learned from “Dog on Sunny Grass” and try “Kangaroo Hopping.” Again, the tail is important. Humans don’t have a tail, but we can imagine the long extension of our spinal columns. The thick muscly tail moves up and down here, the long neck extends in the leap. The front arms are loose, the legs create a strong qi movement in the lower abdomen.

- Now imagine being the joey in the pocket of the jumping mother kangaroo. How it feels to experience the hopping of your mother as part of yourself. The rebound, the temporary weightlessness. The monopedal, directional strength.

- Follow me one more step to this question: Do humans experience our bipedal nature starting from the womb? Directing our energy as an alternating current, walking stimulates a left/right exchange throughout our bodies. Imagine your own legs, feel them walking, how it changes your brain when you relax and let the current evenly flow.

Training our bodies and minds through this kind of cybernetic exploration, this project asks how we might fine-tune the human body for off-planet living as well as mitigate the off-planet environmental and existential stress, learning to cope with current conditions but also imagining new ones. The new frontier in cyberfeminist and trans-species thinking is exactly this idea of a body-mind’s ability to overcome its physical limitations, to inhabit alternate forms.

The next time I “went to my laboratory” in the tank, I discovered the sea creatures. Relaxing as my body began its tick-tock process, I visualized the hammerhead shark, swimming leisurely with mouth ajar, the eyes so far apart that my whole forehead opened, revealing to me my Anja Chakra. With the mollusks, that violent clapping sensation from my first experience was now a process of feeding, gathering energy, which occurred when I was almost falling asleep; the gentle undulations of the jellyfish gathered qi in my lower abdomen, a reservoir called the “dantien,” its tentacles tingling in my legs along the Kidney Meridian.

That day in the tank, I realized we have more weightless moments in our lives that we realize.

I have only seen design ideas for restraints and tight chambers to encourage astronaut sleep in microgravity. What If that confinement is, on some subtle level, damaging? What if there was another way to encourage these resting qi movements?

As simple as the act of lying down for an intentional, observational 30–60 minutes seems to be, what better laboratory to understand the weightless body? Through this engagement, at the very least, if not solving design problems, I think we can foster compassion toward creatures, the land, and our fellow humans, and come into empathetic communication with the qi of the Earth. I have frequently connected my work in the realm of space travel with the idea of home, homelessness, refugee status, and exile. With the imagination of the loss of the Earth, we are grounded in our experience here, whether we ever learn to replicate that off-planet or not.

Carrie Paterson is an artist working in research, olfactory creations, sculpture, and didactics. Find more about her work at her website.